"The children

came from all walks of life, while many were well dressed and actually

very intelligent, most really were in a deplorable state. They were filthy,

their clothing was absolutely disgusting and many were ridden with disease.

It was almost as if they had just stepped out of the book 'Oliver Twist',

it was almost impossible to believe that these children came from our capital

city."

Bernadette Jamison in

her essay "And the Children came to Lancashire".

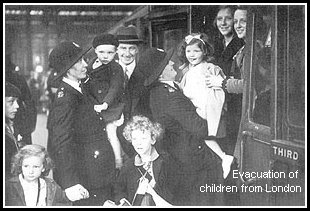

Even before the war had been declared on Germany,

is was envisaged that the prime target of Germany would be the city of

London. The government then had devised a plan that all children, and all

those women that were not on any form of service should be sent to safer

areas of Britain away from any area that could be classed as dangerous.

The places where these evacuees would be sent would be the safer places

of the many English shires. mainly in the country areas away from any major

town or city that was under the threat of being bombed. One of those encouraging

the children to leave possible target and industrial areas was a young

Princess Elizabeth, now the Queen of the United Kingdom. She broadcast

to the young in a program on the BBC called "Children's Hour".

Click on the Real

Player icon below to download a copy of the sound file to your computer so

that you can play it on your own media player.

But although many children had been evacuated

in the early months of the war, the biggest armada of evacuees left London

starting at 5.30am on the morning of September 1st 1940. Included

in the evacuees were: children up to the age of fifteen, mothers, expectant

mothers, elderly and frail people, hospital patients and blind people.

The government orchestrated a scheme where it was possible to apply for

evacuation assistance, and they made all the necessary arrangements regarding

future accommodation and travel. But many decided they would make their

own arrangements, in fact figures show that one and a half million took

advantage of the government scheme, while two million made their own independent

arrangements. Posters were to be seen all over London advising "Mothers,

send them out of London" with a picture of helpless and forlorn children

looking up in bewilderment. All major railway stations were choked to capacity

as trains on altered timetables, plus additional trains that had been scheduled

to move the great armada of children out of London.

|

In all cases the destinations

were kept secret. Even the method of departure varied from place

to place and family to family. One woman exclaimed that at the time of the

evacuation, she was only twelve, and that it was a strange feeling to be

marching even with your mother down the street of the suburb that you lived

in ready to join an assembled crowd at a pre-determined point, and the

strangest feeling being that you did not know where you would be going.

It may have been just to a quiet village just outside London, or you may

have been taken north out of harms way.

|

A very elderly lady explained how she did not want to Leave London, mainly

because her family was still there, including her husband who was stationed

nearby, but it was best that she get the children away in the interests

of safety. She spoke about how she cried as she said good-bye to the children

not knowing if she would ever see them again. But to them, it seemed to

be different. They were ushered from one place to another with large name

tags pinned to their overcoats and a gas mask dangled loosely by their

side, but surprisingly, many of the children seemed to be happy, they were going away,

somewhere different, a holiday....away from the bombs. They were relishing

the fact that they were going to do something that they had never done

before.

THE CHILDREN'S BAGGAGE:

For the most part, mothers and/or parents

were told to take their children to their school playground which was the

assembly point. The photograph at the top of the page shows a typical child

in evacuation dress. Parents were given instructions to place a large name

tag to the front of the child with their name clearly printed. They should

make sure that their children had a gas mask that was to be carried on

the child in its case, and not placed in an enclosed suitcase. They should

have at least two changes of underwear, a night-dress or pyjamas, a change

of socks and/or stockings, a spare pair of shoes, and toiletries that should

include a bar of soap, a toothbrush, toothpaste, a towel, a comb and brush,

handkerchiefs and a warm coat and jumper.

A separate bag should contain enough food

that would last the child for the day. The child was to have only the amount

of luggage that he/she could carry and no more. Most of them carried a

suitcase and had had anything up to three large bags hanging from their

shoulders. All baggage had to have the child's name printed in large letters.

The school playground reception areas seemed

to be chaotic, hundreds of parents and children not really knowing what

to do and where to go. Many sought the advice of "officials" who promptly

asked, 'surname?' then depending to the first letter of your name you had

to register in a certain queue. This was where many of the children got

irritable, children do not like standing helplessly in queues at the best

of times, and being loaded down with luggage did not make things any better.

But, many of them did start to make new friends while breaking the boredom

of just doing....nothing. Parents and mothers too, started conversations

with total strangers, and many questions started to be thrown about which

of course, no one had the answers.

"I wonder where they will be going ?" "Who

are they going to stay with, going into houses, or into boarding type schools

?"

"I wonder if brothers and sisters will

be split up ?" "What will happen if anything happens to them, or what if

anything happens to us ?" There were so many questions, and nobody knew

the answers....except the authorities.

"The

feelings amongst the mothers was generally quite orderly, naturally many

were upset at parting with their children, many were crying and hugging

their children. But the children's behaviour was quite different. Some

remained very quiet tightly holding onto mums hand possibly really not

really knowing what was going on. Others were quite happy, especially when

the time came for them to part from their mothers, which was extraordinary.

Oh there were a few that burst into tears and "I want my mummy" but in

general the children seemed to feel much better when they were left amongst

themselves."

George

Clarke, ARP official at a Bethnal Green reception point.

WHEN TEACHERS ACTED

AS MOTHERS:

In charge of the

children during the evacuation process, were the teachers. These done a

marvellous job and like many others, were among the unsung heroes of the

war. This first day was to be an extremely heavy day for them. Not only

had they the task of organization of the children, but the responsibility

as well. They had to answer all sorts of questions, they had to comfort

those that became upset, they had to control those that got out of hand,

and they had to make sure that all the children were present and that their

name tags and their luggage conformed with the required criteria. At each

interchange point were they had to change from one transport to another,

they had to make sure that all children were present and that none were

missing, and to then organize them to proceed in an orderly fashion to

the next meeting point.

Children nearly always

confided in the teachers, with the movement of so many children the process

was only moving slowly, so teachers very often became mothers or fathers,

and apply themselves to such duties as comforting some, organizing others

yet maintain a well drilled outfit so that even the children at least had

an idea as to what to do next.

One on the train

that was to take them to their new home, more problems came to light. On

the short journeys, railway carriages had no corridor and it presented

a problem of being able to keep an eye on all the children at the same

time as others were in separate compartments. Certain children had to get

out at certain stations along the way, this was a decision that was only

known to the authorities and not the teachers.

On the longer journeys,

most of the carriages had corridors where the teachers could keep an eye

on their flock, usually one teacher from one school to a carriage, although

in some cases schools shared carriages so that there were often two or

three teachers from different schools to a carriage. Queues often formed

at the toilets, and many children did not hurry themselves, and many a

time a child had wet or messed themselves, and it was the teacher that

had to find clean underwear, wash the child and make sure that the child

was once again comfortable. It must be remembered, that in normal circumstances,

trains on long distance were often express and non-stop, but with so many

additional trains, some running one behind the other, long trips were slow

and tedious. Many trains came to a halt, usually just prior to a junction

and stayed there for almost half an hour before slowly moving on again.

There was no such thing as timetables in this time of evacuation.

So where were the children sent to? Even

on the train, the children did not have any idea as to where they were

going, The parents were told that all children were being taken to "somewhere

safe", but that could be anywhere. All different thoughts went through

peoples minds as to where "somewhere safe" was. 'How far away would they

be going?' 'When shall we see them again?' 'How will we know were they

are going?. Questions that were thrown around and around and around. All

the parents were told was that as soon as the children were settled, they

would be informed as their whereabouts.

WHERE THEY WENT:

|

|

| AREAS WHERE CHILDREN WERE EVACUATED FROM: |

| 1. London |

241,000 |

| 2. Manchester/Salford |

84,343 |

| 3. Merseyside |

79,930 |

| 4. Newcastle/Sunderland |

52,494 |

| 5. Birmingham/West Midlands |

32,688 |

| 6. Leeds/Bradford |

26,419 |

| 7. Portsmouth/Southampton |

23,145 |

| 8. Sheffield/East Midlands |

13,871 |

| 9. Teesside |

8,052 |

|

| AREAS

WHERE CHILDREN WERE EVACUATED TO: |

| A. Lancashire |

71,484 |

| B. Sussex |

67,541 |

| C. Yorkshire |

50,593 |

| D. Kent |

38,000 |

| E. Cheshire |

38,000 |

| F. Essex |

25,000 |

| G. Northamptonshire |

24,000 |

| H. Hertfordshire |

23,500 |

| I. Suffolk |

23,000 |

| J. Somerset |

21,000 |

| K. Surrey |

20,000 |

|

|

The above map, and the figures indicating

the child movement numbers is taken from "Life in Wartime Britain" by Richard

Tames which was supplied by Mr Dave Davis. Accurate figures are always

hard to come by but my reference sources state that three million children,

mothers, hospital patients and blind people were evacuated from congested

areas to areas of safety. In "London Goes to War - 1939" by Gordon Bromley,

it is stated that between 1st - 3rd September something like six hundred

thousand children accompanied by their teachers left London for safe billets

in the country. All we know is that thousands of children left areas that

would be classed as dangerous and were evacuated to safer areas in country

districts in Britain.

HEALTH AND WELL BEING OF THE CHILDREN:

It has been well documented that many

of the children, described by many of their new foster parents were dirty,

unkempt, and not only were they dressed in filthy and shabby clothes, they

were covered in lice, mites and skin diseases.

Lifestyle in the country, was a far cry

from that of the big cities and towns including London. Very few houses

in London had a bath, let alone a bathroom. In many cases it was a weekly

chore to walk to the local council bathhouse and queue up for your weekly

bath.

But the areas being evacuated were the

highly populated areas of the cities. Most of the children came from slum

areas, and the east end of London was typical of this. Boroughs such as

Hackney, Bethnal Green, Shoreditch, Whitechapel, Wapping, Limehouse, West

Ham, East Ham, Leyton and Poplar were areas where most of the men worked

in the docklands, at the power stations and at the large factories of John

Knight's soap works, the rubber works at Silvertown, the Leathercloth works

at West Ham and the chemical factory of A. Boake Roberts at Stratford. Men

worked long hours for just average pay and being as owning your own house

in the east end was just about unheard of, most lived in rented accommodation.

No houses had a bathroom, so as I have previously mentioned, a weekly visit

to the local council baths was routine with most families. Toilets in the

house was also something that was unheard of in most cases, usually these

were outside in the cold and dark of the back yard.

So when the children were moved to country

houses, they found quite a difference in the type of houses that were built.

Many of the country homes had hot running water, children could not understand

how hot water could come from a tap.

"I

remember it was so different from our house in Stepney. There were two

of us who had been evacuated to this house in the Chiltern Hills in the

west country. This house had a bathroom and an indoor lavatory upstairs.

It was wonderful having my own towel hanging on the door, and all the toiletries

were on the side next to the wash basin that even had hot water. A long

white bath was to one side which also had hot and cold water that you could

control while sitting in the bath, quite different from the council baths

where the hot and cold controls were outside and you had to call out to

the attendant that you wanted either more hot, or more cold water. I think

the only thing I didn't like was that I had to bath three times a week

instead of only once, but we soon got used to it and enjoyed it."

From

an interview with Ron Collins on his experiences as a boy during the war.

But London was not the

only area that had slums, Glasgow, Birmingham, Liverpool and Southampton

were also some of the areas that were classed as slums. This caused many

of the new foster parents to start making complaints. Up until now, they

had experienced healthy and clean living, now the children that suddenly

came into their homes brought filth and disease, and they were afraid that

such diseases would be transferred to their own children. Many of the so

called "middle class" country people made bitter complaints to the government,

and others even formed protest groups trying to get the message across

that the organization of children from city areas coming to the country

is totally inadequate and that a remedy must urgently be sought to alter

this. One organization The National Federation of Women's Institutes reported

that '....although that this situation related to only a small proportion

of the evacuee's, the problem is but nation-wide and we must make this

intolerable situation known'.

But the children

soon adapted to their new way of life. They learnt what the meaning of

cleanliness was, they adapted to the new lifestyle, and many learnt new

basic skills because many were living on country farms.

EVACUATIONS OVERSEAS:

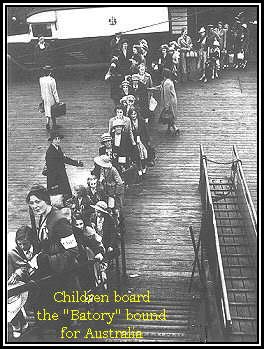

As well as children being sent to the

many safety areas in rural Britain, there were an estimated 3,100 children

that were sent to the commonwealth countries of Australia, Canada, New

Zealand and South Africa. These children were evacuated under a government

scheme called the Children's Overseas Reception Board known as CORB for

short.

Before the war broke out, the British government

had received a letter from a family in Southern Rhodesia stating that due

to the unrest in Britain, and with the possibility of a war breaking out,

that it would be a good idea to send children to the various Dominions

within the commonwealth for the reasons of safety. It does appear, that

the government did not favour the idea at the time and the letter was "filed"

with a note attached saying that it was a good hearted suggestion, but

the whole idea was impractical. Later, as the threat of war loomed closer,

similar letters were received from Canada and Australia.

When war did eventually break out, the

question of sending the children to commonwealth countries was brought

up in parliament. Again the proposal was rejected saying that by doing

so, it would create panic and would be seen as defeatism., and that the

question of overseas evacuation was not a pressing one at the moment. The

government decided that the evacuation to rural areas of Britain should

continue as it was felt that this was quite adequate. The idea of overseas

evacuation was then shelved.

A number

of times the issue kept surfacing in parliament, and the man to whom the

issue was left to "sort things out" was the Member of Parliament for the

seat of Norwich, Geoffrey Shakespear, and was now in the newly formed cabinet

of Winston Churchill. At first, Shakespear was not entirely in favour of

such a project, but by the middle of 1940, with many children already billeted

to rural Britain, he had changed his mind, and became a central figure

in the organization of the Children's Overseas Reception Board.

But as he pushed for the establishment,

others were to knock it down, even Churchill was not in favour. On 17th

June 1940, at a meeting in the War Rooms at Westminster, the proposal

was again under discussion. Churchill again took the defeatist attitude stating that in his opinion, ships at sea would very quite vulnerable to an enemy and that it would be impossible to assign any warships to escort these ships.

Later the meeting was interrupted by a messenger who handed Churchill an

urgent note.

|

|

The note was to inform the Prime Minister

that France, had made the decision to sue for peace, France

was to fall to Germany, and Churchill knew that at this time, Britain

was alone, and with Germany's continual push to the west, the

next target would have to be Britain. Shakespear left the meeting on 17th

June not knowing as to whether CORB had been approved. No motion

had been put forward for it to be passed and/or accepted. But in reading

the minutes of the previous days meeting, Shakespeare found the "the War

Cabinet agreed that the scheme be announced in answer to a parliamentary

question the following Wednesday, and that the Committee report be published."

The proposition of CORB was now ready to be tabled.

Already, it had been estimated that over

10,000 children had been sent overseas privately, but there is no accurate

record of this. But as soon as CORB was made public, it became inundated

with in excess of over 200,000 applications. The scheme was in existence

for only two weeks, and had to refuse any further applications and closed.

In all, 3,100 children were evacuated under

the CORB scheme during July and September 1940 to Australia, Canada,

New Zealand and South Africa. The transportation of shipping at that period

was dangerous, German U-boats were operating in the Atlantic and many convoys

became victims of these German hunters. Two ships carrying CORB children

were sunk by enemy raiders. One was the Dutch Liner Volendam that

had 320 children bound for Canada. Leaving Britain with convoy OB205, that

consisted of 32 other ships. On August 30th 1940 at about 11.00pm

the convoy was attacked by U-boats, and U-60 fired her torpedoes with one

of them going right through the Volendam. All lifeboats were safely

dropped and the 320 children were rescued. Other than the ship, the only

other casualty was the ships purser who was killed.

On September 13th 1940, the

liner City of Benares that was carrying 90 children bound for homes

in Canada, left Liverpool with another liner Diomed carrying 18

CORB male evacuees and a huge cargo of aeroplane wings. The ships were

in convoy OB213 and were 1000 kilometres out into the Atlantic and in an

area noted for U-boat attacks. The weather was bad, and was getting worse.

For some reason, the convoys three escorts had been taken away from OB213

to give protection to some incoming ships, and for the time being, it left

OB213 weak and open to attack. The City of Benares was leading the

convoy, and had no protection and in the inclement weather was making

only slow speed. The ships kept a straight course, not taking any evasive

action in the open sea and were unaware that they were being shadowed by

German U-boat U-48.

In the dark and inclement weather, at

about 10.00pm, U-48 turned towards the convoy OB213, and picked out the

leading ship, the City of Benares. The German attacker closed in

and Kapitanleutnant Heinrich Bleichrodt gave the order to fire two torpedoes.

With an horrific roar, and a sudden column of flame the City of Benares

was torn apart. Turning, U-48 fired more torpedoes and two other ships

in convoy OB213 were hit.

Hurriedly the lifeboats from the City

of Benares were launched, but in the wild weather most of these either

capsized before they reached the water, or they were swamped by the cold,

huge waves. Next day, HMS Hurricane came to pick up survivors, but

all that it accomplished was the collection of dead bodies, casualties

of both the bitterly cold water and the weather. It was by a miracle that

on trying to pluck bodies from an upturned lifeboat that HMS Hurricane

realized that two young girls were still alive, 15 year old Beth Wilder,

and 14 year old Beth Cummings would live to tell of the ordeal of the Benares.

They were two of the 13 of the 90 CORB children on board that survived.

There was outrage within the British government

that children should have been innocent victims of war, Churchill the least

impressed because it was he who rejected the passage of children on vessels

plying in the Atlantic Ocean. In his position, he had more important things

to worry about, but he wanted to know, why was this allowed to happen without

his approval, that the scheme went ahead on a memo that "the scheme was

approved only on as far as it was allowed for a report to be released.

Beth Walder told of her ordeal later, but

what were the thoughts of those parents who lost their children, what were

the feelings of those naval personnel of HMS Hurricane who realized that

it was young children they were plucking out of the cold waters of the

Atlantic. It must have been horrific.

The Ordeal of

Bess Walder

The

night was absolutely horrendous. It was the blackest of nights, and it

was raining and the wind was blowing at gale force. The lifeboat's keel

was the only thing available, so our hands locked onto it. There was a

row of hands alongside mine, on my side of the keel -- and another row

of hands on Beth's side, facing -me. Bit by bit the rows of hands grew

less and less as people lost their grip, or lost their will to live --

and let go.

We knew that if we could hang on until daylight things would be better.

We made up our minds -- we were just going to go on hanging on, despite

everything. Obviously in the later stages we were fantasizing. We saw what

we thought were enormous fish, we saw icebergs, we thought we saw ships,

we thought we saw planes. We had had nothing to drink and nothing

to eat, and we were suffering from severe exposure... I think we were very

near death.

It was getting dark [on the evening after the sinking], and Beth and

I had both made up our minds that this was probably going to be our

last day. But there, coming towards us, at a very very creeping speed,

was a black dot on a previously blank horizon seen over the crests

of the waves. And unlike the other things we had seen this was definitely

moving towards us. This one was real. I croaked to Beth, 'Beth, there's

a ship'. When we were finally rescued they had to prise our hands off the

keel.

Beth Walder / Edward

Stokes Innocents Abroad

CONCLUSION:

It would be safe to say that more than

a million children had been evacuated out of the cities and the large industrial

areas. Wherever it was felt that an area was declared as being unsafe,

parents were advised to move their children out. It was a hard time all

round, while many children were well dressed and healthy, there were others

that only had dirty clothes and suffered many skin diseases. These were

the ones that had come from the slum areas, many children did not even

take changes of clothing with them and it was up to the new foster parents

to provide new and clean clothing and seek medication for many, and this

was done out of their own pockets.

Many children found it strange in their

new surroundings and were very nervous, they had known no other parents

except their own, and in the country areas the rural lifestyle was completely

different to which they had been used to. But many settled down in the

new environment and stayed for the duration of the war, while others were

taken back by their families as life was still "normal" in places such

as London and in other big cities. The heavy bombing that had been forecast,

never came.

When Christmas was the time to be with

loved ones, many children were taken back home to their parents, but of

all those that went home, a quarter of them stayed and did not return to

their foster parents. The government started asking that parents should

pay a contribution towards the cost of keeping the children, naturally

most were poor and could not afford it, and slowly the children went back

to their parents, by 1944, most evacuations had ceased despite cities still

being bombed, and the evacuation scheme was terminated.

But evacuation was not without serious

problems. On a number of occasions while the children were in the safe

haven of the rural areas, their parents had been killed in the "Blitz".

One could not expect the temporary foster parents to adopt them as their

own, although in a number of cases it did happen. But most were sent to

orphanages which soon became overcrowded. After the war many were shipped

to orphanages overseas, to such places as Australia and Canada, which were

run by church and catholic institutions, but now it is being revealed that

in Australia many of these children had been subject to sexual misuse by

Christian fathers, but because of impending inquiries that are now being

looked into I cannot and am not at liberty to reveal any more than that.

Some children were told that their parents

had been killed in air raids when the truth was that they hadn't, these

too were sent to orphanages overseas. Only recently a war orphan was reunited

with his brother after 55 years, only to be informed that their parents

were not killed during the war, their house was bombed, but they had taken

refuge elsewhere and survived. Again, I cannot report any details. But

it happened, many children and parents were told lies and the outcome was,

that they were never repatriated with their families when peace finally

came to Britain.

With the temporary foster parents, things

were hard for them as well. When asked at the outset of war that would

they take in a child from the cities, they not only felt sorry for the

children, but the British way of life was "Let's Stick Together", they

were going to do their 'bit' by taking the children in. They were not expecting

to house children that had no changes of clothing or were ridden with disease,

many just took it in their stride and got the children cleaned up and re-clothed

them at their own expense, but others complained and said that disease

ridden and dirty children were not welcome to the clean life of the country.

Yes, it was hard all round, and we must

not forget the parents who had to let their children go. Where would they

go, would they be safe, and when will we see them again. But it was all

part of being British, it was the civilian way that they were going to

fight this war. This was war on the ground, no one missed out on fighting

the war, from mothers to generals, everyone had a part to play.

WOMEN AND THE ELDERLY:

Women who did not have occupational work

in the cities were also advised to leave and evacuate to safer areas. Many

of them would not leave their homes and demands by the authorities were

constantly being made on radio and in newspapers that it was not safe for

them to stay in areas that would be targets for the enemy in the event

of bombing raids. Many took heed of pressure by husbands, friends and the

government and made the move to rural areas, only to return many months

later as there was no sign of the cities being bombed.

There were many that

returned to the cities, many of them coming back prior to the Blitz in

September 1940 as they thought that Germany would not bomb the cities after

all. Many took the elderly with them, to care and look after them in more

secure parts, but the main problem of returning while the war was still

on was the fact that they could have been returning to homes that had been

bombed, or had even disappeared. This then presented problems and additional

worries for the authorities. The usual answer was that they must return

back to the country areas from where they came, as only after the war would

they have time to be able to assist them.

SOURCES

Stewart Ross Home Front

1960

Edward Stokes Innocents

Abroad

Gordon Bromley - London

Goes to War 1939. Michael Joseph 1974 |