BATTLE OF BRITAIN one of the |   |

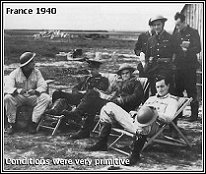

PRELUDE TO BATTLE

253 Squadron was formed at Manston in November 1939, almost entirely from the Airspeed Oxford pilots from Brize Norton. We all travelled down together from Brize to find that the squadron consisted at that time of two Magesters and that we had 2 flight commanders who had come from other squadrons, one being Guy Harris and the other H T J Anderson, and the CO was called Elliott. Other than that the whole squadron comprised of pilots who had just finished their training at Brize, 90% of them being on Airspeed Oxford’s.  Feb: 9th. 1939: Reported to No 11 ERFTS Perth Scotland. Our course of about 30 were trained on Tiger Moths, by civilian instructors for about 10 weeks in which time we had to solo within 12 hours, and practice flying and aerobatics for about 50 hours. April 15th. 1939: left Perth for RAF Uxbridge for uniform fitting, drill, and discipline for two weeks. May 1st. 1939: We were all posted to No 2 FTS Brize-Norton in Oxfordshire, here we were divided into two lots, those to train on single engine North American Harvards, and those to train on twin engine Airspeed Oxfords, it was my lot to be on twins. There for 6 months I flew 80 hours duel and solo, during which time I did four hours dual, and 2 hour solo night flying, navigation cross country's, forced landings, aerial bombing and machine gun firing at Porthcawl armament camp, after which we were awarded our wings, and posted to our new units in November. 253 Sqdn was originally to be a Blenheim squadron, but at that time it was found that the RAF was woefully short of fighters, so imagine my delight to find myself where most of us wanted to be, - on a fighter squadron; even if we hadn't got any planes. Socially our six months at Brize Norton, was very pleasant, everything that you ate or drank was billed at the end of the month, and was very cheap, dinner at night was a "must" on four nights a week, two in mess kit, and two in dinner jackets, the other three nights were in mufti, or eat out. I was half way through training when war was declared. Nov. 11th, 1939: 253 formed at Manston, the only aircraft we had were two Magisters. It was not until Jan. 1st 1940 that we were given some Fairey Battles to train as fighter pilots, since there were no Hurricanes available. February 10th, 1940: I flew a Hurricane for the first time. February 16th, 1940: 253 Squadron moves to Northolt. May 9th, 1940: 253 Squadron moves to Kenley. May 16th, 1940: "B" Flight moves to Manston, en route to Lille Marq, France. May 17th, 1940: arrive Lille Marq. May 19th, 1940: evacuated Lille in the afternoon, having shot down a 109 in the morning, only three aircraft flew home, the rest were broken up being u/s. We had lost our flight commander on the 18th, he was killed. Meanwhile "A" Flight had gone to Vitry, where they had lost their flight commander Guy Harris, wounded, other pilots were also killed and wounded in both flights; by May 19th we were all back at Kenley. May 24th, 1940: 253 moved to Kirton in Lindsey, Lincolnshire, with new C/O S/Ldr Tom Gleave, and both new flight commanders F/Lt George Brown, and F/Lt Bill Cambridge July 9th to 18th, 1940: "B" Flight attached to Ringway Manchester for defence purposes. July 22nd, 1940: 253 moved to Turnhouse, Edinburgh, joined by new C/O S/Ldr King, Tom Gleave remained as supernumerary. August 23rd, 1940: 253 moved to Prestwick. S/Ldr King left us and was replaced with S/Ldr Starr. Tom Gleave still remained. August 29th, 1940: 253 Squadron left for Kenley. August 30th, 1940: Was our first action in the Battle of Britain, we lost three pilots. December 9th, 1940: I was posted away from the squadron. From the diary account above, to a more detailed description of events commencing with our moving to France from Kenley: WE'RE OFF TO FRANCE Six days afterwards we moved from Manston to Northolt and there we stayed flying Hurricanes until on May 9th we moved to Kenley, by which time I had accumulated 64 hours flying time on them. These Hurricanes were the original ones received from the squadrons, with the old wooden props, (only coarse pitch and fine pitch), and no mirrors or armour plating! On May 16th an Ensign arrived at Kenley and “B” Flight, of which I was a member, were told that we had to move our all our kit into that aircraft and that we were going to France! We were told to take everything with us, to clear our rooms out, and that we would be leaving that afternoon, following a Blenheim. We would stay overnight at Manston and carry on to France the next morning. “A” Flight was remaining behind. Eventually we loaded everything into the Anson and we took off and flew to Manston. This was just “B” Flight, under a Canadian called Anderson. The CO stayed behind with the Adjutant. We flew behind the Blenheim to a turnip field called Lillemark. We were supposed to join up with a flight from 111 Squadron which had also been split, which was a little bit upsetting. We landed at Lille early in the morning. We were left on our own at the edge of the turnip field where we tried to join forces with 87 and/or 504 Sqn but they wouldn’t have anything to do with us as our aircraft were not up to standard! At Lille the squadrons were all over the place all around the field. Our radios were the old TR9s which had a range of 2 miles if you could hear them at all, and were absolutely useless! When the air raid siren went off in Lille itself we were supposed to take off. The first time that happened we had just landed and refuelled. We all took off and aircraft came from all directions from all over the field and how we missed each other I don’t know. There was simply no organisation whatsoever. However, we joined up and tried to follow anyone we could see, whatever squadron it was! Eventually we managed to find our way back again and landed. That night we slept on stretchers in a tent, there was no proper accommodation for us, we were freezing cold just lying on the stretchers in our flying gear, no blankets, and we got no sleep at all.  An airfield somewhere in France in the spring of 1940 where the comforts of home had been left behind and now with not even the basic necessities conditions are primitive as those that were there will tell you. The next morning, standing in the early mist and cold, I saw 2 Lysanders, Army Co-op machines, making their final approach to land. Suddenly, out of nowhere, four Me 109s just pulled in behind them. I remember hearing no sound whatsoever but as they flew away both Lysanders dived straight into the ground, both going up into a huge burst of flame. That was my initiation into air warfare and I wondered what had hit me. WELCOME TO FRANCE I was then separated from all the others, found myself alone, and went down to the first airfield I could find. I saw aircraft on it and discovered it was Meurville. I was completely lost as I had no maps. I was refuelled and then returned to Lille. The next day all our aircraft were supposed to take off and rendezvous with some Fairey Battles and escort them to Cambrais. We took off and climbed to 15,000 feet which seemed to be the fighting height in those days, but found no Battles. Then we suddenly engaged enemy aircraft and we all got split up again. Once again I was on my own, trying to find out where I was, when an Me 109, all on its own passed 100 feet below me. This time I had my guns and my sights on, (I was now putting them on before I took off, otherwise I’d forget), and I dived after the 109, came up behind it and gave it a long burst. But our guns were loaded with de Wilde ammunition which gave off a white puff of smoke rather like tracer only more accurate. It shook me, it looked just as if the German was firing 8 guns backwards at me! I could see my shots going into the 109 but it looked as though it was coming back. It scared the daylights out of me until I realised what it was. I continued to fire until my guns were empty and the 109 continued straight on down into the ground and the pilot did not get out. I found my way back to Lille and shortly afterwards we were told that there was a possibility that we would have to evacuate. By that time we had lost three of our pilots, Sgt G Mackenzie (L1667) buried at Cysoing, our Flight Commander, Flt Lt H T J Anderson (L1674) buried at Lille, and P/O F W Ratford (L1660) buried at Reincourt, all shot down by Me109s of JG3 at approximately 10.30am. Shortly after that we were told to evacuate and return to Kenley, as we were surrounded on both sides by the Germans. There where only three aircraft fit to fly, and myself Curly Clifton and Pete Dawbarn flew them back while Jenkins took the party by road to Boulogne with all our kit, so all I had left with what I was standing up in - my uniform. Apparently, when they got to Boulogne they were told to toss everything off the quay into the harbour, and were allowed only to take rifles and what they were standing up in back to England. So my golf clubs are now at the bottom of Boulogne harbour, under several feet of mud I should think! But we found out when we got to Kenley that “A” Flight and Guy Harris had gone to Vitry where they would fly during the day and return at night to England. During their stay there they got badly beaten up. Guy Harris was in hospital with a bullet in his back and he stayed there for about five or six months before he was ready to fly again. Jimmy Ford was shot down and lost an eye and a lung and he never flew again. Radford was killed, and there were several others, I cannot remember their names. Anyway, during all that, the CO, Elliott, and the Adjutant had stayed in England and seen none other fighting whatsoever. But of course, once we got to Kenley and the troops were retreating to Boulogne on the 21st, I was flying as No. 2 to Squadron Leader Elliott, jinking around to avoid the flak. There were no enemy aircraft, but as I turned around to go back I found that he had disappeared. I didn’t see him go, neither did anyone else. Anyway, we found out many years later that he had landed behind enemy lines as he did not want to fight the war any more, and that he had finished up as a prisoner of war. We found that out years later from Allan Corkett, who was shot down in July 1943 and sent to Stalagluft 3. There he met Squadron Leader Elliott, who told him that he hadn’t wanted to fight anymore so he had landed behind enemy lines and surrendered. On the 23rd we had to escort some Ensigns over to Merville, they were picking up things, and we got into a big battle over there. I shot down a 109. On the way back it was very misty over the Channel and I continued to fly westwards. After half an hour I thought ‘Gee whiz, I should havebeen over land a long time ago’ but there was no land to be seen. Then I thought that I was probably flying along the Thames estuary. If not, I thought, I must be flying south, so I turned the aircraft around and flew north and within five minutes I hit the coast. I saw an airfield and landed on it and just as I taxied in I ran out of petrol. I had landed at Ford aerodrome in Sussex. THE SQUADRON REBUILDS AFTER FRANCE There were, of course, a lot of new pilots. Each day, as Dunkirk was going on, Atcherley was on the phone trying to get our squadron back down into the fighting, as he wanted to get into it himself, but we didn’t want to go back at all! However, Air Ministry soon got on to that and Batchy was only with us for about five or six days and he was posted north to Wick. Upon which he was replaced by S/Ldr Tom Gleave who was a really nice person, and later became a good friend of mine. We continued training there until we went up to Edinburgh. There they posted in a new C.O., Sqn Ldr Eric King, and made Tom Gleave supernumerary. It appeared that, for one reason or another, they did not want Tom as C.O., probably because he had been ‘flying’ a desk for so long! Anyway, King didn’t last for long and soon moved to 249 Squadron. He seemed to be a very peculiar sort of chap the short time he was with us. We then moved to Prestwick near Glasgow, but on August 8th 1940 Tom was once again replaced as C.O., this time by 25 years old Sqn Ldr Harold Starr. Meanwhile through August the Battle of Britain had been getting fiercer and fiercer and we all wanted to get back down there again and get into the fight. But some of us who had been through the Battle of France knew that it wasn’t half as glamorous as it sounded in the newspapers and on the wireless. THE SQUADRON MOVES INTO BATTLE The next day we flew another two sorties, during which S/Ldr Starr was killed. The following day S/Ldr Gleave was very badly burned. Early in September Bell-Salter and Sgt Metham were both shot down, injured and hospitalised. We had lost both our C.O.s so Bill Cambridge was now acting C.O. P/O Clifton was killed shortly afterwards and L C Murch was shot down uninjured. On 4 Sept F/O Trueman was killed; on 5 September Samolinski was shot down but uninjured; on Sept 6 Bill Cambridge was killed; on Sept 9 F/O Watts was shot down but unhurt; Sept 14 Sgt Higgins was killed; Sept 20 P/O Barton was wounded and Sgt Innes shot down but unhurt; Sept 26 P/O Samolinski was killed and F/Lt Edge, who had taken over as C.O., was shot down and injured; Sept 29 P/O Graves and Sgt Edgely were both injured; Oct 10 Sgt Allgood was killed; Oct 11 P/O Murch was injured; Oct 15 Sgt Key was shot down but unhurt, as was P/O Novak; and so it went on. Coming back to the beginning of the Battle of Britain, our biggest problem was that we didn't have a good leader. Tom Gleave was a very brave man but he was not a good leader. Starr had no chance to show his worth as he was killed very early on. Bill Cambridge was not very good either, but when we got Gerry Edge he proved to be the best leader we had. On Sept 9 we had one attack with nine aircraft, we went line abreast, head on, against about 36 Ju88s. I was flying Number 2 to Gerry Edge, and I still dream about that attack. I fired one burst, it couldn't have been more than two or three seconds, and then pushed the stick forward and the enemy aircraft passed overhead, it couldn't have missed me by much. Nobody claimed anything at all from that encounter but we found out later, after the war of course when we got hold of German records, that our Squadron had shot down five enemy aircraft in that attack.! That was a great attack, it was really good leadership, but unfortunately Gerry Edge was himself shot down a few says later. We then had a chap called Duke-Woolley as C.O., who had come off Blenheims. But he was really learning the ropes himself and on 15 September, when we should have been flying at 25,000 feet, he was leading us around at 15,000 feet, and we were watching all these aircraft above us, where it was mayhem! All that action and there we were stooging around 10,000 underneath them! When we eventually landed I asked him what the hell we were doing at 15,000 feet and he said, oh, I thought we were supposed to be there. I really flipped and as I was only a lowly Flying Officer and he was a Flight Lieutenant he wasn't too happy about that. From the time the squadron was formed until then, not one single Distinguished Flying Cross had been awarded to our squadron, which was an absolute and utter disgrace. Out first DFC was awarded to Jerry Edge on 13 September. He thoroughly deserved it, if only for that attack on the Ju88s. Later on, in November, just before I left the squadron, apparently Fighter Command asked our C.O., Duke-Woolley, since we had no other medals, to submit the names of two pilots to be awarded DFCs. He then named himself and a chap called Eckford. In October we used to leave Kenley early in the morning and operate all day from Hawkinge. It was an awful period since no bombers were coming over, only fighters at round about 30,000 feet, and we would have to take off into the sun, climb up into it and there were many pilots shot down and killed, quite uselessly in my book, it was not a good time at all. Anyway, that was the way it was. The Battle went on and I remember on one occasion towards the end, after an engagement, finding myself alone, yet again, this time at 28,000 feet, which was a bloody stupid place to be. Anyway, I looked up and four Me 109s passed over the top of me just a 100 feet or so away, the best target I had in my life. So I pulled the nose up, had my sight and guns on, and I fired, but as I did so I stalled and spun. I suppose I was only flying at about 80 mph and it only needed that little extra to spin me. I have no idea if I got a part of a 109 as I saw nothing as I spun down. In November I was posted to an OTU and that was the end of my time with 253 Squadron, which was exactly one year. Looking back now, it is my opinion that we were treated disgracefully as a squadron and I cannot understand why Dowding has got a memorial when things like that happened. To split a squadron up into two halves, without their C.O., sending them to different places, only half trained at the time, when I look at it now, we had the worst aircraft out in France, we were the only ones without mirrors and without armour plating, and yet we shot down during that time, and the subsequent Battle of Britain, a good many enemy aircraft. Yet not one of our pilots, many of whom served in both battles, was awarded a DFC. which, once again, was another disgrace. But I suppose it was because we lost so many leaders that there was no one around to recommend anybody! Well, as you can tell, I am still angry about it all, a very angry old man! For what they did to our squadron and for what they didn't do for our squadron. Sixty years on and the visitor to Kenley can still see some of the area left behind on the site of the old aerodrome. Most of the old buildings have long disappeared, but shown above is the remains of the wide east-west concrete runway just as it was many years ago. Grass and weeds are now showing in the joints between concrete layers, but as one stands in the centre of this long runway, it is not hard to let your imagination run wild, and you can hear the sound of Merlins being warmed up by the hangars that would have been behind us and to our right, or men walking to the operations room or to the officers mess that would have been on the extreme right although out of view in this photo. Some scars of where the bast pens used to be are still just about visible around the perimeter, although the entrances to some of the air raid shelters still exist and can be seen just as they were left at wars end. The sight of a squadron of Hurricanes coming up this runway and taking off would have made my day, but there are things that even the imagination cannot do, and this would have been one of them. |