The Royal Air Force drew

its pilots from a number of sources. As well as the regulars, and those

on short service commissions from Britain and the commonwealth countries

there were others that formed the University Air Squadrons as well as the

auxiliaries.

During the early part of the Battle of Britain,

Royal Air Force relied mostly on the reservists and the part time flyers

who were the mainstay of Fighter Command. Most were either young, 'green'

and under trained or had been with the RAF for so long that they were actually

past their peak, although if we look at the records we would find that

many of the 'aces' were actually over thirty years of age. The cream of

the British fighter pilots for some reason were transferred to Bomber Command

between the two world wars and at the outbreak of the Second World War

it left Fighter Command in a rather dilapidated position.

Quite often we are accustomed to seeing the fighter pilot in silk lined flying jackets with silk scarves bellowing in the wind as they race around in their open wheeler two seater

sports cars and with their public school education throw out remarks like

" I say old chap, did you enjoy that pancake with the Spit?". News and

film media have always displayed the role of the fighter pilot in this

fashion, but actually out of the 3,500 Fighter Command pilots that took

part in the Battle of Britain, only about 200 had received a public school

education. 601 Squadron had a number of these, and the parking lot at Tangmere

used to look like a starting point for a 'concours de elegance' with brightly

coloured MG's and Austin Healey's looking in far better shape than the

Hurricanes that they flew. It has been said that these pilots actually

bought the local service station so as to keep their cars on the road.

Most of the pilots came from much humbler backgrounds, there were bank

clerks, young doctors, factory workers, shop assistants and hundreds who

had just ordinary jobs. Many of these were given a hard time by the educated

contingent and quite a bit of resentment followed. So do not be fooled

into believing that most Fighter Command pilots spoke in university and

educated fashion as many movies depict as most of them came from just ordinary

backgrounds. But, they did, as other branches of the services had, a certain

form of sayings and terminology spoken within the RAF:

bellowing in the wind as they race around in their open wheeler two seater

sports cars and with their public school education throw out remarks like

" I say old chap, did you enjoy that pancake with the Spit?". News and

film media have always displayed the role of the fighter pilot in this

fashion, but actually out of the 3,500 Fighter Command pilots that took

part in the Battle of Britain, only about 200 had received a public school

education. 601 Squadron had a number of these, and the parking lot at Tangmere

used to look like a starting point for a 'concours de elegance' with brightly

coloured MG's and Austin Healey's looking in far better shape than the

Hurricanes that they flew. It has been said that these pilots actually

bought the local service station so as to keep their cars on the road.

Most of the pilots came from much humbler backgrounds, there were bank

clerks, young doctors, factory workers, shop assistants and hundreds who

had just ordinary jobs. Many of these were given a hard time by the educated

contingent and quite a bit of resentment followed. So do not be fooled

into believing that most Fighter Command pilots spoke in university and

educated fashion as many movies depict as most of them came from just ordinary

backgrounds. But, they did, as other branches of the services had, a certain

form of sayings and terminology spoken within the RAF:

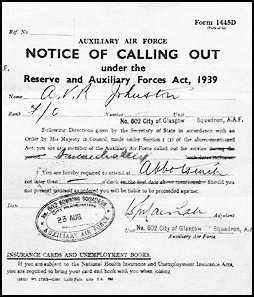

Pilots were called up to serve in the RAF in a number of ways, many applied to serve with the Royal Air Force after seeing the many recruitment posters displayed all over Britain. Quite a

few were already serving with the RAF while others already belonged to

University Air Squadrons such as Oxford, Cambridge and London, and Eton

although only a school, was very well represented with many Etonians

going to the other University Air Squadrons. Many, after having part time

training belonged to the Auxiliary Air Force and these pilots were given

'Calling Out Papers' like the one shown above that was issued to 'Sandy'

Johnstone who was directed to report to 602 City of Glasgow Squadron. Another

was Australian born Pilot Officer Richard Hillary who attended Oxford University

who went to 603 "City of Edinburgh" Squadron. Many of these pilots flying

for the first time together were sent to France, some immediately became

heroes like Edgar 'Cobber' Kain a New Zealander who claimed his first Dornier

Do17 in November 1939, then shot down another Do17 just fifteen days later.

'Cobber' chalked up 17 confirmed victories before being killed in an accident

in June 1940. He was awarded the DFC.

Funny

this was, although I worked in banking, I had applied to get into the RCAF

but it appeared that they didn't want me. With the war just started in

England, I felt that I had a chance over there.

At

the time the RAF were taking just about anybody they could get their hands

on. They had a terrific shortage of pilots, I think half of the pilots

were from the Commonwealth, a lot of us were Canadians. I applied, I got

called up on a Monday, had the medical on Wednesday and sailed for England

on the Friday.

Pilot Officer Alfred

Keith Ogilvie 609 Squadron RAF

Prior to 1939 when the possibility of war

could become a reality, Britain arranged for short service commissions

where pilots that had already received basic and fundamental training,

could further their experience with flying and combat skills. A number

of pilots that undertook this scheme came from Canada and Australia. Many

Australian airmen were trained at the RAAF Training School at Point Cook

in Victoria, and many took advantage of the offer of a short service commission

with the RAF. Many others applied for enrolment into the Empire Training

Scheme and commenced their training in Canada. It was here that they had

the opportunity of selecting whether they wanted to go into Fighter, Bomber

or Coastal Command. An Australian was asked what he would like to be, and

he answered, "I'll be a gunner", to which the desk clerk said "Why do you

want to become a gunner? "All right, I'll be a navigator then" to which

the desk clerk politely asked "Why do you want to be a navigator?" So the

Australian said "Then I'll be a pilot if that's all right with you." And

that's what the Australian got, he saw the war through as a bomber pilot.

Many pilots recorded victories, but in general,

most pilots complained of the condition of the aircraft saying that they

were, in conjunction with the inexperience of the new pilots, no match

for the Luftwaffe pilots who already had considerable combat experience.

"Look,

you've got to face it, France was a shambles. Everyone tried their best,

but most of us pilots were not only new to flying in combat, we were new

to flying in general. If an Me was coming towards you firing all guns,

you would push the stick forward, your heart seems to go up into your throat

as he flies past you. You know he's going to make a tight turn, the

Me was like that, and your ticker would be pounding nine to the dozen as

you looked in the mirror, looked from side to side but couldn't see him,

but you knew he was there, instinct told you he was there. For the new

pilot it was panic stations, okay, we were told not to panic, but it was

human nature. We learnt by those mistakes, your leader might call out over

the radio that the 'hun' was on your tail calling you by your code name,

but in a state of panic, it was not unusual to even forget what your code

name was.

Sgt

G.C.Bennett 609 Squadron. (Later killed in 1941)

The conditions in France

were backed up by many.

"We

were ordered to attack the advancing German columns around Sedan. On

the 11th and 12th May, everybody got back alright. Then on the 13th May

five of our aircraft went again on exactly the same course for the third

day running. Only one came back. After that it was chaos. We did some leaflet

dropping at night. Those of us who were left moved from field to field,

half a dozen times a fortnight. A lot of people just got lost. We ended

up with two other Battles from Squadrons we did not know, alone in a field

somewhere in Central France...........Our aircraft was had been damaged

a good bit by then, but we found another that was missing a tail wheel,

we put our tail wheel on it, pushed the ground crew in the back, and took

off. All I had was a cycling map of Northern France."

Sgt

Arthur Power 88 'Battle' Squadron

As time progressed, many friendships blossomed

between the educated and the ordinary bloke. Soon all were to realize that

they were out there to do a job, and that was to become the master of the

plane that they were flying and move in on the 'Hun' for the kill. As news

came in telling them that someone had not returned, or was missing or killed

in action, they felt as though they had lost a member of their family,

but it was the courage of the fighter pilot that he

would immediately go

down to the pub as if nothing had happened.

"It

was hard when word came in that one of your mates was missing, another

pilot may have given a graphic account of how he saw someone go down in

flames and hadn't a chance to bale out. You sort of somehow found a big

hole in your stomach momentarily. But you could not afford to think of

such matters, you put your mind to other things, you got drunk or whatever.

You train yourself to think of only one thing, and that is the job that

lies ahead."

George

Barclay 151 Squadron.

"We

were all amateurs. Yet the young pilots lived their lives to the full because

they knew that any day they'd be dead."

Gregory

Kirkorian. RAF Squadron Intelligence

"The

waiting was the worst part, we'd sit around playing poker with that tension

pit in our stomachs - it was almost a relief when we heard the phone ring

to scramble."

Group

Captain Peter Matthews.

Life was not easy for the fighter pilot, every

day was a long day, generally up before dawn making preparations for the

day that lay ahead. A day in the life of a pilot [ Document

17 ] was a strain on both mind and body. Some days he was on the go

from before dawn to well after the sun had gone down. He had to contend

with squadron mates who failed to return, maybe missing in action or as

was the usual story, killed in the line of duty. No one knew what the next

day was to bring, most although were intent on claiming victory over the

enemy, they were in fact just fighting for survival, they drank to lost

loved ones then prayed for their own safety.

And why did they do it? According to P/O

H.G.Niven, "All you wanted to do was to fly, we were young and had no real

moral angle, you wanted action because you were twenty or so, you could

fly, you knew how to fly and you knew you had to fly because there was

a war on." But whether or not your prayers would be answered, those that

died as well as those who survived were duly recognized after the war by

being able to display a rosette and clasp [ Document

18 ] on their 1939-45 star indicating that they, as pilots of Fighter

Command took place in the greatest battle of all time, "The Battle of Britain."

It was a different

story with the Luftwaffe. These pilots had received exceptional training,

and Germany was producing some 800 trained pilots a month compared with

only 200 a month in the RAF. Not only that, the Luftwaffe pilots were combat

trained having seen action in such places as Spain, Poland, Norway and

Belgium.

The Luftwaffe had

a comprehensive training program and with so many experienced pilots they

helped and assisted any of the new pilots assigned to their squadrons.

Relations between the officers of the Luftwaffe and the junior ranks were

far superior than that of the RAF and the morale of the men was greater

as well. It was back in 1923 that the Reichswehr-Ministerium (The German

Defence Ministry) signed an agreement with the Soviet Union that allowed

them to set up complete training facilities near Lipezk. Pilots, observers

and aircraft mechanics were sent there to undertake a thorough and complete

schedule of training. With others being trained at the Deutscher Luftsport-Verband

which was a sporting flying club, most of the Luftwaffe personnel were

experience men during the period with the Legion Kondor during the Spanish

Civil War, then later in the conflicts in Norway, Belgium, Holland and

in France.

Before and during

the early part of the Second World War, all German aircrew had to undergo

at least six months basic training, and keeping in line with the strong

Nazi belief in physical training, this included drill, various forms of

sport and light gymnastics. In the classroom, they were taught the fundamentals

of flight and aerodynamics, navigation and the laws of aviation. Prior

to the outbreak of war, the Germans practiced their flying skills in aircraft

that were not visually designed as military  aircraft

in keeping with the restrictions imposed on them by the Treaty of Versailles

way back in 1919, but closer inspection of the aircraft revealed a very

strong military influence. Later more military style aircraft were introduced

and pilots increased their knowledge and skill until they had passed their

basic training and moved on to the advanced training centres where they

moved on to more advanced aircraft, advanced aircraft skills and learnt

more about combat defence and attacking tactics before they were given

their licence. aircraft

in keeping with the restrictions imposed on them by the Treaty of Versailles

way back in 1919, but closer inspection of the aircraft revealed a very

strong military influence. Later more military style aircraft were introduced

and pilots increased their knowledge and skill until they had passed their

basic training and moved on to the advanced training centres where they

moved on to more advanced aircraft, advanced aircraft skills and learnt

more about combat defence and attacking tactics before they were given

their licence.

Those that were training

as bomber crews were transferred to another school where another 60-80

hours were spent undergoing intense training on more advanced aircraft

and then on to specialist training on instrument flying and skills. Once

they had practiced simulation sorties on combat operational aircraft they

were ready to join a Kampfgeschwader (Bomber unit). Potential fighter pilots

also went further additional advanced training and were sent on to mock

air battles before passing out and being allocated to a Jaggeschwader (fighter

unit).

"We

were idealists with the honour of being part of the most elite fighting

force in the world"

said a young aircrew

cadet as along with 3,000 others they were addressed by

Adolph Hitler on their graduation day in the capital Berlin.

"........we

listen to the spell binding words of our leader and accept them with all

our hearts. Never before have we experienced such a deep sense of patriotic

devotion towards our beloved German fatherland. I shall never, never forget

the expressions of rapture which I saw on the faces around me today."

But even the young Luftwaffe pilots admitted

that their early combat duties often disclosed their inexperience. A young

pilot, on one of his very early combat missions came under attack from

RAF fighters:

"It was the first time I had experienced this. . . it was a kind of ticky,

ticky, tick. . but it made me feel good that it had protected me. Anyway,

what I did was evade whoever was firing at me by nose-diving. Now, I thought,

I've got rid of it, so I climbed up again trying to catch up with the unit.

I remember thinking, Well, this isn't so bad . . . The protection had held

. . . but I was still climbing and suddenly there was a second attack from

behind. It was so fast that I couldn't evade before it came . . . at least,

I as a beginner couldn't. Suddenly he was there and immediately I went

down again. While I was diving I thought, Well, what do I do now?

Some pilots said that in such a case you just go down to tree-top level

and go home . . . but I thought, Well, that sounds too easy, so I decided

to climb up again.., which was a big mistake that an experienced man would

not have made.

Then as I was climbing again suddenly I was attacked from below to the

right-hand side. Someone who was more at home playing these games had come

from below from the right-hand side. In this area there was no protective

armour so it was a real problem.

The glass from the cockpit was splintering, the instrument panel splattered

and now I was really hit. . . or many hits. Somehow at that point I blacked

out.

When I came to I found myself in a vertical dive and what I noticed was

lots of noise, a kind of fluid coming from the side of the plane and what

struck me was that the ground was approaching very fast. I realized that

I had to catch the plane immediately and get it out of the dive. I did

and in doing so my blood rushed from my head and I blacked out again. When

I came to I found I was at tree-top level with little power left in the

machine. It could still fly but with no power. I was now very, very low

and had to look for somewhere to land.

At this stage I looked around and found that there were two Spitfires behind

me and they were shooting occasionally, but I guess it was difficult to

shoot at me because I was going so slow and was not flying in a straight

line. I don’t know whether they didn’t shoot me because they saw I was

in a difficult situation....anyway, I just saw an English park-like landscape,

some bushes and trees. There was a group of trees ahead of me and I said

to myself, Well, gee, what I have to do is to try to get enough speed by

flying directly at the trees and then hope that I have enough speed to

jump over them and then go down. I did this and then blacked out once more.

Bruno

Petrenko ex Bf109 pilot now living in Canada

[Ben

Wicks Waiting For The All Clear Bloomsbury Publishing 1990

p26-27]

German pilots generally

had far more training than the British, even during the period of war,

Luftwaffe training was intense, where the RAF just could not get their

pilots into the air quick enough. The reason for this was that the RAF

had a shortage of pilots and aircraft. If you had a months training, then

you were one of the lucky ones. A few weeks learning the eliminatory physics

of flying at a desk, usually up to about 15-20 hours actual flying, and

you were posted. Most learnt the best way (sometimes not the correct way)

to fly and be successful was the actual experience gained in combat flying.

But flying was only one part, evasion tactics in combat was another, and

a "good pilot" you had to be a good shot to shoot down one of the enemy

and evade being shot at yourself, and this was not always that easy.

"We learned tactics pretty quickly, but there wasn’t much time during the

Battle. We learned to spread the vics. One chap was put in as ‘weaver’

— arse-end Charlie — weaving about behind our formation, keeping look-out.

They were often shot down, weaving behind and never seen again.

Sailor Malan was the best pilot of the war, a good tactician; above average

pilot and an excellent shot. In the end it comes down to being able to

shoot. I was an above average pilot, but not a good shot, so the only way

I could succeed was to get closer than the next chap. This wasn’t easy

Johnny Johnson was a pretty good, average pilot, but an excellent shot.

The answer was that there were was no really successful shooting parameter

above 5 degree deflection. Most kills were from behind, coming down on

the enemy, or head-on, or in 5 degrees deflection.

The Spitfires guns were harmonized to about 450 yards, but this was spread too far across. Sailor

Malan trimmed his own guns down to 200-250 yards, and we all followed suit.

At the end of the day, you had to have luck, and I had my share. Once I

had my watch shot off my wrist. It was my own watch, and the Air Ministry

wouldn’t pay me back for it! Another had a bullet hit his headphones. His

ear was a bit of a mess, but at least he was alive.”

Air

Commodore Alan Deere CBE. DSO. DFC. ex 54 Sqn, 602 Sqn and 611 Sqn RAF

Trimming your guns down

to 200-250 yards, not easy, but effective if not daring. And you must remember

that the Spitfire was traveling at over 300 mph and that 200 yards would be covered in just a matter of seconds. There again, many experienced pilots trimmed their guns down to even less and others opened fire exceptionally close to their targets.

Squadrons

of Royal Air Force Fighter Command were made up of a variety of types.

As well as the regular squadrons, there were the voluntary squadrons, the

auxiliary squadrons, the Fighter Interception Unit and some Fleet Air Arm

units.

The majority of the pilots were of British nationality although it has now been found that many pilots from commonwealth countries, because they carried British passports and not one from their own country were classified as British. Canada immeadiately responded by sending many pilots, but Australia and New Zealand did not officially make any contribution of pilots. Only those pilots that were serving on short service commissions with the Royal Air Force from Australia and New Zealand were to fight during the Battle of Britain and represented their respective countries.

The United States, because President Roosevelt was campaigning for re-election of the presidency would not get involved with the war in Europe despite many pleas from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The American government also would not sanction any American citizen going to Britain to fight the war in Europe. Seven men however defied United States law and each of them made their way to Britain to join the Royal Air Force and fight in the Battle of Britain.

With the fall of various countries in Europe, many experienced pilots from the air forces of Czechoslovakia, Belgium and Poland made their own ways, many under very difficult circumstances in an effort to get to Britain and join the Royal Air Force. Because of the number of pilots that had made their way from their invaded countries to Britain, the RAF was able to establish individual squadrons such as the 303 Polish and 310 Czech squadrons. Canada was also given their own squadron which was 401 Squadron that originally was 1RCAF Squadron but was renumbered so as to avoid confusion with 1 Squadron RAF. Australia, New Zealand, United States and Belgium did not have their own units during the Battle of Britain but later in the war all these countries were to have their own squadrons.

|