|

The Chronology: Page-41

Details of the mornings action |

Sunday September

15th 1940, was not only the turning point of the Battle of Britain, it

was the turning point of the whole war. Every Fighter Command aerodrome

in 11 Group was in some way involved, every squadron within 11 Group participated

as well as the Duxford Wing from 12 Group and a number of squadrons in

10 Group were called upon to protect areas in the south west. Ground crews

at all 11 Group airfields had to make efficiency a top priority in getting

aircraft refueled and rearmed in between sorties, while at 11 Group Headquarters

Air Vice Marshal Keith Park busily controlled the situation drawing on

all his experience and expertise under the watchful eye of visiting Winston

Churchill who saw first hand the development of activities on this important

day. Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding remained at Fighter Command Headquarters

keeping silent vigil over the large map below indicating to him the events

and the unfolding battle that was taking place over the south-east of England.

For Adolf Hitler and the German commanders, time was now running out. If an invasion was to take place on September 17th as planned, the lead-up would have to commence no later than today.....September 15th. The weather had shown, just how quickly it can turn at this time of year, and with winter not too far away, the German forces would have to take advantage of the better conditions that now seemed to prevail. Göring had sent out the instructions the day previous to all bomber and fighter bases that preparations for an all out assault on England was to be made on this day September 15th, bomber units were given times and flight paths of their attack. Over the last few weeks, the Luftwaffe had experimented with different flying formations, needless to say, none had really been successful, losses had still been high, but they had discovered that on the occasions that they had kept at high altitudes, they had on a number of occasions surprised Fighter Command. This was mainly due to the fact that the British radar was ineffective above 20,000 feet, and by flying at a height above this level they could cross the Channel undetected, but, the Germans did not know this. All that they were aware of, was the fact that those formations that flew at higher altitudes were not intercepted until they were usually well over the English coast. The most logical reason for this, thought the Germans was due to the fact that it took the British fighters much longer to gain the required height to intercept. The sending of advance Ju87 and Bf110 units to bomb the radar stations along the southern coastline was, in the opinion of the Luftwaffe, a waste of time. As fast as they seemed to be destroyed, they were back in operational use again, and mobile units too were brought in to replace any radar station damaged. Over the last few days, the Germans had practiced at electronic jamming, this, they believed was successful and plans were made to intensify the jamming procedure in an effort to further reduce detection. The spirit of the German aircrew, was still far from high. Time and time again, they had been told that the 'Glorious Luftwaffe' is ready to strike the final blow. But they had been told that in July, and again in August when Adlerangriff had been announced, and it was to be repeated yet again this September 15th. Early in the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe aircrews were told that the Royal Air Force would be wiped out in two or three weeks, now, whenever they fly over the British countryside they are still met with masses of British fighters in the hands of pilots that were gaining in skill and techniques. Many firmly believed that they were no nearer victory than they were two months previous.

In Britain, things

were slightly different. Most of the pilots were relatively fresh unlike

their German counterparts. Combat action had been very infrequent, with

only one really heavy day. As mentioned previously, Fighter Command was

now stronger than it had been for weeks, aerodromes repaired, planes and

personnel had replaced many that had been shot down and the radar stations

were all functioning at 100%.

Park meanwhile, was prepared. He had learnt just a few days previous that there was to be a large scale attack prior to the impending invasion, only that he was unsure as to the exact date or time. Whatever attack that the Germans planned, he was sure, that 11 Group was ready even though the Luftwaffe commanders could not agree as to the actual strength of Fighter Command at the time.

To survive any

intense attack that may be instigated by the Luftwaffe, Keith Park had,

in the last few days rearranged some of his squadrons, carefully placing

them in the best strategic position to provide the best defence of London

that he possibly could. Of course, we must remember, that the pilots of

Fighter Command had no idea of any large scale attack being made by the

Luftwaffe. This information was only known by a selected few in radio interception

(the "Y" Force) and the Air Ministry and of course, Dowding and Park himself.

To the pilots, any change they thought was the usual relieving of tired

squadrons.

[ Document 52. ] September 15th Order of Battle It was not long after breakfast that Keith Park new that today was to different from all others, for the first time in a week, he had been notified that there was a build up of German formations along the enemy coast. 'This, I think is what we have been waiting for' he said, ' I think that it is about to happen.' WEATHER:

Heavy cloud and rain periods overnight was expected to clear and the forecast for the day was fine in most areas with patchy cloud. No rain was forecast but some areas could expect an odd shower to develop. The cloud was expected to clear during the afternoon giving way to a fine and clear evening. OPERATIONS

IN DETAIL:

0900hrs:

Unaware of what was about to unfold within Fighter Command, the British

Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his wife decided that he would call

upon Air Vice Marshal Keith Park at 11 Group Headquarters at Uxbridge.

Keith

Park took his visitors to the operations room, and as he began to explain

some of the complexities of the operations, a radar report had come through

that a number of enemy aircraft had been detected building up in the vicinity

of Dieppe, another smaller formation had been detected over the the Channel

off the coast near Dover. Park told the Prime Minister that he was lucky

because it looked like that he could witness the activities of operations

because a couple of German formations had been spotted. Winston Churchill

replied that he would let the C-in-C carry on with his job and that he

would just sit and watch.

The C-in-C called up some of his station commanders, mainly at Biggin Hill, Kenley and Hornchurch and ordered that they each place a couple of squadrons on 'Stand By' *. All eyes were concentrated on the large map table below. The smaller formation seemed content on staying out of reach in the centre of the Channel and made no move towards the English coastline. "Feelers," said Keith Park, "no doubt trying to entice our squadrons into the air." He knew that there was something strange about this morning. A small formation, possibly Bf109s flying parallel to the coast while a larger formation was gathering behind them. These tactics had not been employed since they used to make attacks on his airfields. The markers indicating the position of the enemy force near Dieppe on the map table were now pushed into a position near the centre of the Channel, their strength was forty plus, and he now noticed that another marker had been placed slightly behind and to the left of the first marker. This also read forty plus but for both markers, there was no height reading. Another call to his station commanders, and more squadrons were to be placed on 'Stand By' * while others were placed at 'Readiness' ** Should the detected formation decide to abort or pose no further threat the order of "Stand Down" *** would be given to any, or all squadrons. [1] * "Standby"

(pilots strapped into their aircraft with all connections intact ready

for immediate take off.)

0930hrs: The two formations had spread themselves out and were detected near the coasts off Dover, Harwich and in the Thames Estuary. Squadrons were dispatched from Hornchurch, Gravesend and Croydon. But most of the German formations were ordered to turn back. The Fighter Command squadrons were recalled. The only other activity was just off the Devon coast were a lone reconnaissance aircraft was detected and a flight from 87 Squadron Exeter (Hurricanes) was "Scrambled". It turned out to be a He111 on weather reconnaissance and was shot down by P/O D.T.Jay. 1030hrs: New formations were detected positioned between the towns of Calais and Boulogne. The markers on the map table at 11 Group HQ indicated that the enemy strength was 100 plus, but within moments, another marker was placed just behind the first and indicated 150 plus. It appeared that the German formations were in no great hurry and were forming up very slowly, this worked to the advantage of Keith Park as it gave him the chance to organize his defence forces. "This, Mr. Prime Minister looks like the big one." said Park, eyes glued to the map. The C-in-C gave a few orders then asked for someone to get Observer Corps HQ on the telephone, then he ordered his assistants with him to get the various sector station controllers "on the blower" with the order for all squadrons to, "Stand By". During a lull in Parks orders, Winston Churchill, standing beside him said quietly, "There appear to be many aircraft coming in." Keith Park answered in the same low tone "And we are ready for them.......there'll be someone there to meet them." 1100hrs: The picture now of this morning attack was clearer. There was at least 200 plus bombers and an unknown number of Bf109 and Bf110 escorts just off the coast near Calais. They were flying in a nor' nor' west direction and in a straight line this would allow them to cross the English coast in the vicinity of Dungeness. The expected time over the English coast would be between 1145 and 1200hrs if they were carrying heavy bomb loads, which it was expected they were.

Park was expecting

a heavy engagement, but the map showed no other detection of enemy aircraft,

just this one coming towards Dungeness, and this was big enough. He asked

his assistants to get the sector controllers on the phone again and in

the next thirty minutes, the following squadrons were scrambled:

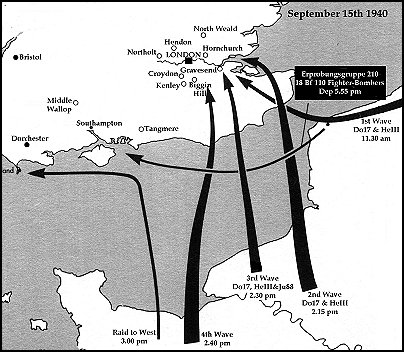

1130hrs:

Just as the first Fighter Command squadrons approached the southern coast

of Kent, the leaders of the German formation still had a few miles to go

before they crossed the tall cliffs of the British coastline. The enemy

bombers consisted of practically the whole of 1/KG76 flying Dornier Do17s,

these had met up with the Do17s of 111/KG76 and KG3 behind Calais and now

the combined force, escorted by Bf109 escorts formed a vast armada almost

two miles wide crossing the coast. All the enemy aircraft were thought

to have departed from bases in the Brussels and Antwerp areas. The heights

of the enemy formations were between 15,000 and 26,000 feet and the Observer

Corps reported that they were crossing the coast just north of Dungeness,

to the south of Dover and at Ramsgate.

The bombers came across the coastline in a number of vic formations, some of these consisted of three aircraft, some in five while others were in vics of seven, but as they crossed the tall cliffs they looked something like a giant herringbone. The bombers, which consisted of Dorniers, Heinkels and Junkers were escorted by Bf110 aircraft flying in close support while the Bf109s flew top cover high above the bombers. Keith Park reckoned that the advance squadrons should make the initial interception and slow the advancing formation down. He knew that it would be asking too much to turn such a large force around and it would be obvious that these squadrons would have to be replaced as fuel and ammunition became low. The relieving squadrons then would leave London defenseless so Park decided to bring in the 'Duxford Wing' from 12 Group and wanted to vector them to be over London just prior to the estimated ETA of the enemy formation should they manage to get through. In the next fifteen minutes, the following squadrons were scrambled:

1200hrs:

The German formation was making slow progress and 72 Squadron Biggin Hill

(Spitfires) and 92 Squadron Biggin Hill (Spitfires) were vectored to intercept

the enemy between Maidstone and Ashford. Some of the other squadrons that

had been vectored further south were now re-vectored. These included the

Hurricanes of 253 Squadron Kenley and 501 Squadron Kenley, with the Spitfires

of 66 Squadron Gravesend, 603 Squadron Hornchurch and 609 Squadron Warmwell

and within minutes reinforced 72 and 92 Squadrons. Soon after the initial

interception, 229 Squadron Northolt (Hurricanes) and 303 Squadron Northolt

(Hurricanes) met the raiders between Rochester and South London while 17

Squadron Debden and 73 Squadron Debden (Hurricanes) met the bombers over

Maidstone. Fighter Command had eleven squadrons engaging the German armada.

The heavy bomber formation was still stepped between 15,000 and 25,000

feet with a massive Bf109 fighter escort above and slightly to the rear

of the main formation.

The combat action was exceptionally heavy, and most of the defending British fighters managed to keep the Messerschmitt escorts from providing the cover for the bombers. The using of paired squadrons as requested by Keith Park was working. The Spitfires harassed the Bf109s, criss-crossing them at every opportunity, and one by one they were sent spiraling towards earth trailing plumes of smoke. The Bf109s tried to continue to escort the bombers who now were being attacked by the Hurricane squadrons. The British fighter pilots were slowly breaking up the formation with a steady application of force causing the bombers to straggle out of formation. [2]

The hundreds of

Bf109s covered a wide area and they too were having their successes. Two

Hurricanes of 229 Squadron were shot down over the Sevenoaks area, with

P/O G.Doutrepont aircraft being shot up badly and he was killed as the

Hurricane went down and crashed on Staplehurst Railway Station. Another

member of the squadron, P/O R.Smith managed to bale out of his bullet riddled

aircraft also over Sevenoaks and he suffered severe leg injuries. Over

Tunbridge Wells, F/O A.D.Nesbitt of 1 (RCAF) Squadron was swooped on by

Bf109s and he baled out as his aircraft spiraled to earth. F/O R.Smither

was not so lucky, as he went down with his aircraft also over Tunbridge

Wells.

The combat area now covered a wide area, and as the minutes ticked by, the intensity of the battle increased as more fighters of Fighter Command arrived on the scene. 501 Squadron Kenley (Hurricanes) was one of them. They intercepted the enemy over northern Kent and mixed it with both bombers and fighter escort.

Squadron Leader

John Sample went on to say, that soon after this, he came across another

Do17 that had been hit by a Spitfire and a Hurricane who were following

closely and was trailing white smoke. Not that one could really get bored

up there, but he had nothing else to attack, so he climbed up above the

Dornier and then made a diving attack. As the distance between himself

and the bomber narrowed, he noticed a red light in the rear-gunners cockpit,

but as he got even closer, he saw that he was looking through the whole

length of the inside of the Dornier to the pilot and observers cockpit.

The red light that he saw, was in fact the red glow of fire. He gave another

short burst, and as he turned and went past the aircraft, the inside was

nothing but a red hot furnace inside. He then saw it go into a spin after

the tail section broke away, followed by the wing sections beyond the engines.

The narrow fuselage with short stubbs of wing roots fell though the cloud

to oblivion, John never saw it crash.

Another pilot of 504 Squadron, Sergeant R.T.Holmes, decided that he would take on no less than three Dorniers at the same time. The first, after a short burst bellowed smoke, but as he flew past he got a spray of black oil on his windscreen. But that did not deter him from going in on a second Dornier ahead. Another short burst as the Do17 was lined up in his sights, and smoke and flames came from the stricken bomber and it dived away. He then took on a third, but soon afterwards, his Hurricane banked sharply and he lost all control, he started to go into a wild spin. It is not known as to whether he collided with the third Dornier, or was hit by enemy gunfire but he found it difficult to extract himself from the doomed fighter. Suddenly, he managed to free himself and jumped, the parachute breaking his fall just twenty feet or so above the rooftops of some houses in fashionable Chelsea. His backside hit the sloping roof of one of the houses, and he began to slide down the roofless, fall off over the guttering and straight down into the garden below, and into a garbage bin. The Dornier came down about a mile away crashing into the forecourt of Victoria Station, practically demolishing a small tobacconist's shop. [3] 1215hrs: The Bf109s were being held over the northern area of Kent with only a few managing to escape the onslaught by the Spitfires. The bombers which consisted of He111, Do17s and Do215s were being harassed by the Hurricanes, and one by one they began to turn away smoke trailing from engines and desperately trying to evade any further attack by the British fighters. Others dropped their bombs at random. Some of the more courageous tried in vain to make it to their target, riddled with bullets, crewmen either dead or injured at their posts. But more was in store for them as they approached London. Keith Parks timing of requesting the Duxford Wing to cover the airfields of Hornchurch and North Weald was to perfection, as was everything else that was taking place. It seemed that Fighter Command could do no wrong. As the German bomber formation, with about only one third of its Bf109 escorts, approached the outskirts of London the enemy was in disarray. The Bf109s peeled away one by one, some had sustained damage but most were now low on fuel. With the city now in their sights, they were confronted by the most awesome sight of the four squadrons of the Duxford Wing. Three squadrons of Hurricanes with the two Spitfire squadrons about 5,000 feet higher. As the Duxford Wing closed in, they were joined by 41 Squadron Hornchurch (Spitfires), 46 Squadron North Weald (Hurricanes), 504 Squadron Hendon (Hurricanes) and 609 Squadron Warmwell (Spitfires). The Bombers were confronted by British fighters on all sides, and one of the biggest combat actions ever seen over London developed. Sergeant D. Cox of 19 Squadron wrote in his combat report:

Where

everything was running in favour of 11 Group, for once, Douglas Bader's

'Duxford Wing' also ran to perfection and in unison. Bader stated later,

that being called up with time to spare made all the difference. His squadrons

were able to take off as ordered, and the formation collected perfectly

over Duxford and 56 fighter aircraft made the steady climb towards their

vectored area, and had time to position themselves at the correct height

and head towards Gravesend. As they approached the Thames, the Hurricanes

stepped between 25,000 and 26,000 feet with 19 and 611 Squadron Spitfires

at the rear climbing to 27,000 feet, they could see the little black specks,

like a small formation of little ants in the sky. Douglas Bader led his

'wing' in a partial semi-circle allowing them to arrive at Gravesend with

the morning sun behind them, and the Germans in front. But it was not until

reaching the western boroughs of London did the 'Duxford Wing' manage to

engage the enemy.

Perfectly positioned, with the bombers 3,000 feet below them they were about to make their attack, when a formation of Bf109s came out of the sun. Bader immediately ordered the Spitfires of 19 and 611 Squadrons to take on the German fighters, which they did so effectively, scattering them by a surprise attack that they left the bomber formation and flew off to the south-east. While the 'Duxford Wing' were holding, the Hurricanes of 257 Squadron Martlesham and 504 Squadron Hendon (Hurricanes) attacked the German bombers. Bader waited for them to complete their sweep, then instructed his three Hurricane squadrons to fall into line astern and prepare to attack. Bader selected the most westerly of the three enemy formations, while 302 Squadron took on the middle formation while the remaining formation was left to 310 Squadron. [4]

There was not much

for the bombers to do, the pressure on them was intense. They would be

attacked by a couple of squadrons of RAF fighters, then as soon as they

broke off the engagement, another couple of squadrons were ready to pounce

at an already decimated enemy force. The bombers began to drop their bomb

loads at random hoping that this would lighten their load and they could

make as hasty retreat as possible without any further damage to their aircraft.

South London was the worst affected, with Lewisham, Lambeth, Camberwell

and a couple of the bridges across the River Thames all recording bomb

damage. One high explosive bomb fell in the grounds of Buckingham Palace

causing slight structural damage to the building but a bigger hole in the

lawns at the rear as it failed to explode. A power station in Beckenham

was also hit.

The German formations headed out towards the west, turning south near Weybridge. 609 Squadron Warmwell (Spitfires) chased them as they headed for the coast and took on 15 Dornier Do17s, a formation of Bf109s saw the desperate situation that their bombers were in and joined in as did a few Bf110s. Over Ewhurst in Surrey, 605 Squadron Croydon (Hurricanes) came in to assist and as the mêllée continued fierce action over the town of Billingshurst just west of Horsham they were joined by 1(RCAF) Squadron Northolt (Hurricanes) who took on the troublesome Bf109s. In the other direction, some eighty German bombers were trying to make good their escape towards the Thames Estuary. Fighter Command attacked in large numbers with squadrons attacking any of the escorts while others took on the merciless bombers. The first, and the morning battle had been a disaster for the Luftwaffe, many cashed, others blew up in mid-air, while the remainder struggled for the safety of the French coast. [5] For the Germans, after about ten minutes over London, there was now no such thing as the formation. German bombers were at all levels of altitude and most were scattered over an area fifteen miles wide. To give an example of the intensity of this morning battle, the combat area was approximately 80 miles long by 38 miles wide, and up to six miles high. Total combat actions numbered as many as 200, one third of these were settled within the combat area with one of the aircraft submitting either by being destroyed by his enemy or a disabled aircraft managing to break away and head for safer pastures. The other third was with German aircraft being chased away from the combat area by British fighters and often crashing on English soil or going down into the watery graveyard of the English Channel. Because of the intensity and aggression shown by the pilots of Fighter Command, the bombers dropped most of their bombs randomly over a wide area. Damage was done, but not as much as was intended by the Luftwaffe commanders. For the Luftwaffe, the raid was doomed to failure the moment that the first formations had crossed the Channel. This time, everything had gone right for Fighter Command and 11 Group. Timing, position and height was all on the side of the RAF. Keith Park and his pilots had won the first round of the day.

1230hrs:

As the clocks in Britain showed 12.30pm, the first battle of the day had

finished. Most of the German bombers who had intentions of again dropping

hundreds of tons of bombs on the city had been fought off by Fighter Command.

In scattered areas of Kent and Sussex the odd skirmish still took place

as patrolling squadrons observed a few Dorniers and Heinkels desperately

trying to make their way back to their bases in northern France and Belgium.

The pilots of the Hurricanes and Spitfires showed no mercy. It made no

difference whether the bombers were crippled or not, some, which it was

obvious that they would never make it back, were shot down, the broken

hulks of German aircraft could be seen from the outskirts of London to

the Channel coast.

.

To many Londoners, many were out and about on this fine day in September, and went about their business as usual, the dog- fighting high above being little more than entertainment value. There is no doubt, that again the

Luftwaffe were their own worst enemies on this mornings raid. Too many

aircraft being dispatched from a rather enclosed area of Calais, the manner

in which they organized their formations over the Channel, it was too cumbersome

and too slow, and again, Göring did not value the worth that radar

had for the British. All the time the enemy bombers and their escorts were

forming up, Fighter Command had a birds-eye view of the proceedings that

was going on across the Channel. It allowed Keith Park the time he needed

to organize his squadrons, paying particular attention to which squadron

was to be vectored where. Of course, it also allowed him to call on the

'Duxford Wing' giving them more than the time required to form and be in

the right position at the right time when they made their interception.

As battle weary fighter pilots returned from the mornings operations, they were unaware that a second attack by the Luftwaffe would be made early that afternoon. As each squadron landed back at their bases, the normal rearming and refueling procedure was carried out, pilots, after being interviewed by the intelligence officer lay back in the midday sun, to relax, unwind and to share experiences of the morning success. For some, it would be less than an hour before they would be called on again as the next wave of enemy aircraft had been detected. [1] Vincent Orange

Sir Keith Park Methuen 1984 pp109-110

|