| Document-4. |

|

SANDBAGGING

Shops, public buildings and some monuments

suddenly became hidden behind hordes of man made sandbags. This was one

of the first precautions that was undertaken in protecting buildings from

the perils of a bomb blast. Many shopkeepers placed sandbags across their

street frontages, and also took steps to strengthen their basements, so

that in the event of an air raid customers would feel secure. It paid dividends

to the shopkeeper too, because shoppers gave preference to shops that had

the necessary precautions, and many thought it a wonderful gesture on behalf

of the shopkeeper. If there was an air raid, then customers would feel

far more secure in a shop that had precautions than being caught out in

a shop that had none at all.

In some of the larger stores, especially those in such places as Piccadilly, Regent Street, Oxford Street and High Holborn they converted underground store rooms into large air raid shelters, and even employed their own air raid wardens and security personnel. Stores such as Selfridges and C & A's which normally had long glass front window displays were completely boarded up with timber panels and sandbags. Sand and soil was brought in from various places in and around London, and one of the most popular excavation sites was on Hampstead Heath, where large channels were dug by cranes and mechanical excavators. Other places that were a source of supply were the many sports grounds and parks and once sand and soil were excavated it was taken by lorry to various points around the city and men, women and even children volunteered to undertake the filling.

But the sandbags would only give protection to the lower floors,

the upper floors, because of their height, could only have

their windows boarded up and taped to avoid any splinters of glass from

entering the wards should a blast penetrate the windows. any splinters

of glass from entering the wards should a blast penetrate the windows.

THE ANDERSON SHELTER

With such a vast population, London had

to have some form of shelter for its inhabitants. The building of communal

shelters in various parts of the city was an action decided against because

should such a shelter receive a direct hit, then a greater number of people

would be killed than if there were a form of shelter that could be used

for individual use. A number of communal brick and steel mesh shelters

were constructed, and these were placed in various streets throughout the

city as seen in the photo in the title. They were long, generally had entrances/exits

at both ends, were about thirty to forty feet long and could accommodate

up to a hundred people, although uncomfortably. Most of them were damp,

cold and miserable, they had no windows and even the outside daylight was

diffused because a security wall separated the entrance from the shelter.

|

|

|

|

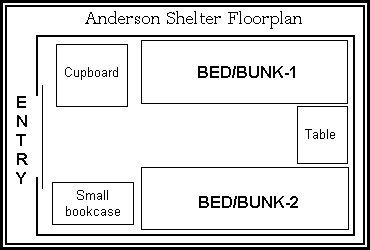

It was the Home Secretary Sir John Anderson

who devised a plan that a simple shelter could be constructed with the

use of six curved corrugated steel panels with five flat corrugated panels

and that they could be assembled easily by the home handyman and that they

could be installed in the backyard of any home. First, a shallow square

hole had to be dug in the ground of the backyard, this usually measured

about ten feet by four feet. Then you erected the six sides bolting them

together, the curved ends formed the roof of the shelter. Then the rear

section was put into place followed by the front in similar fashion except

that provision was made for an entrance. Many families placed a raised

flooring system inside so that any water or seepage that got in would be

below the floor. Usually two beds were placed on either side, these may

be single or bunk beds depending on the number of children the family had,

if any. A small table was generally placed between the beds and small cupboards

and bookcases or bookshelves were close to the entryway. There was no hard

and fast way in which the interior had to be designed, this was generally

up to each individual. But you had to take into consideration that being

as you was possibly going to spend just about every night down in the shelter,

you had to somehow stock up with non-perishable foodstuffs, a canister

of water, and if you had children there was always a supply of boxed games,

books and other things to help pass the time.

It was recommended by the authorities that families do not construct toilets in the shelters because of health reasons, but there were not too many shelters that did not have a bucket or a pot at the end of the bed for emergencies. The entrance was normally just a piece of sackcloth, although some handymen managed to make opening doors to their wartime abode. Some exteriors of these shelters also came in for a variety of designs. Many covered the top of the shelter with earth and made small gardens above the shelter where they grew a few vegetables, some were satisfied with just flower beds, while others just painted them. By September 1939, nearly one and a half million Anderson shelters had been distributed without cost to families whose income was less than £250 per year, and they could be erected by either the home owner or the local council. When first erected, they became the pride of many families. High mounds of earth covered the shelter and all over the top was a brilliant display of colourful flowers, while the inside of the shelter was used to do some of the usual gardening chores such as repotting and nursing new seedlings. When the bombing started and families had to use the shelters for the purpose for which they were designed, they took an instant dislike to having to spend all night confined in a small place with very little air circulation, often damp and waterlogged underfoot. Quite often mum and dad took the wise precaution of sandbagging one of the rooms in the house and took the chance on being bombed rather than catch pneumonia, and the Anderson shelter was left to the daughter and her boyfriend for a little privacy.

ran on there was this centre rail that was a live rail that supplied

electricity to the trains. If anybody fell onto this rail they would be

electrocuted, should they also place part of their body on one of the other

rails which would earth them.

The government also thought about the possibility

of a station receiving a direct hit. London was full of gas and water mains,

and should any of these be ruptured, then there would be the possibility

of a catastrophe hundreds of feet below the surface where thousands may

be either gassed or drowned.

But what the government was afraid of, happened during a dreadful raid on the city. Balham station in the south of London was almost to capacity when the station received a direct hit. Another bomb fell on a row of shops above the station and as it exploded the shops fell into the area were the stations underground booking office was. The water mains were ruptured as well as the sewer mains, and gallons of water and raw sewerage poured into the station gushing down escalator stairways, down tunnelled walkways until finally pouring out onto the station platforms where thousand were camped for the night. In all there were 600 casualties that night, the worst underground disaster so far. In another direct hit, Bank underground station in the city proper was another scene of utter devastation, over 100 people died that night. But still the people thronged to the Underground,

to many it became an institution. They would leave home at mid afternoon

knowing that full well that "Jerry" would be back again that night. They

came with rolls of blankets, pillows and cartons of sandwiches and drink

that would see them through the night. They would queue outside the station

until they were let in and it was almost like the January sales as they

pushed and shoved their way down towards the platforms to find a few square

feet of space that they would declare as their own for the next twelve

hours.

But it was not always the underground stations that became the night time hub of sheltering people. Near many of the marshalling yards near to London, and especially in the east end, there were small tunnels and long underground bridges that, although they were being used by rail traffic during the day, at night they became home to thousands who wanted security over their heads.

Whichever way you look

at it, the underground was to most people a way of life, a ritual, and

something that they became accustomed to during the nights of continuous

bombing of London. Later, and during the night when some of the trains

had stopped, many bands came down into the stations and turned underground

stations into music halls with music, songs and entertainment. What a way

to enjoy the war. While other just listened to the radio.

SOURCES

The Battle of Britain - 1940

website © Battle of Britain Historical Society

2007

|